A guide to choosing GCSE English learning resources in a landscape dominated by the AQA English GCSEs.

Summary

- There are many exam boards offering Level 2 assessment of English in the form of GCSE, International GCSE or IGCSE.

- Exam boards tend to present their approaches as being different and, implicitly, better than other exam boards.

- From experience of teaching and examining across a range of various specifications over the years, I argue that the differences are not as huge as they are often presented.

- It is true that, from a primarily administrative/bureaucratic standpoint, the exam boards’ approaches are different (e.g. marks allocations, timings, question styles).

- However, there are major similarities and, with good teaching, I argue that students can find value in resources designed for a specific board but useful for many.

- This is particularly important for students following specifications with fewer available resources (ie not AQA) or for students who have changed education provider during a GCSE course.

First, a look at the numbers

For many students, no choice of exam or exam board is offered. Students will take the qualifications as decided by their English department. For most in England, this will be the AQA GCSE English Language (8700) and AQA GCSE English Literature (8702): 77.6% and 80% respectively in 2019-2020.

This still leaves schools in England who choose other exam boards and also schools in Wales and Northern Ireland who follow the WJEC and CCEA versions of the GCSE English qualifications.

Added to this are some schools, mostly outside the UK, who choose to offer IGCSE First Language English (CAIE) or International GCSE English Language (Edexcel A, Edexcel B, OxfordAQA) qualifications with, where relevant, the related English Literature qualifications.

Then there are the home educated students who are able to choose from all of these options. Most currently end up choosing one of the ‘I’ options as they do not require non-exam assessment (for example the Spoken Language endorsement), which can be difficult to arrange outside a school setting.

Overall, the numbers in these last few categories (Wales, Northern Ireland, international, home education) are small compared to the numbers taking the AQA English GCSEs – c600,000 every year.

The problem

This creates a huge imbalance in the availability of learning resources. Search online or visit any bookshop and the likelihood is you will find plenty of material tailored to the AQA GCSE; you will need to dig a bit deeper to find OCR related material.

I am regularly contacted by parents asking for help finding information, practice papers, model answers for some of the more marginal exam boards.

This situation also causes a problem for me as I create my learning resources. My cohort reflects the numbers above; most of my students are AQA with the occasional CAIE, Eduqas or Edexcel IGCSE B student just to upset the applecart and keep me on my toes.

Certainly, as I build my collection of model answers, I have my AQA students firmly in mind. But what about my other students? I don’t want them to be left out.

Should resource creators also produce versions of resources that precisely reflect the current specifications for the other exam boards as well? Should we produce versions for every English Literature set text (c15-20 texts per board) and for the slightly different ways the same set texts are assessed on different boards? What about when the specifications change?

Lots of questions. What’s the answer?

The solution

My solution is simple and can be witnessed in schools up and down the land and across the globe every day. Where necessary, teachers create specific resources. A set text (e.g. Songs of Ourselves) might only be relevant to one board or there might be really specific exam technique advice valid only for Eduqas GCSE English Language Component 1 ten mark questions that does not transfer easily to other boards.

However, in other circumstances, fruitful use can be made of a range of resources across different boards. For example:

- advice on how to write a short story or indeed model short stories are relevant to every creative writing exam task across the many boards.

- a series of notes on a set text, Macbeth for example, or model essay answers will be really useful for all learners.

- a non-fiction writing past task from one board may well be useful to set a student following another specification, especially when the stock of past papers has run out, as often occurs with keen, hard-working students.

- a set of short literary descriptions that model rich, observant, poetic language skill will be useful to all students.

Of course, some minor adaptations might need to be made. Some minor caveats about differences in exam administration might need to be communicated. For example, the AQA Macbeth essay is marked out of 34 marks; for OCR, 40 marks are on offer.

A good teacher/tutor will be able to navigate this situation and students are, in my experience, very capable of dealing with the concept of mutatis mutandis, though they won’t know it by that name; in other words, they are able to accept and process the necessary minor changes to a learning resource whilst learning greatly from the unchanged material.

Wait. How is that possible? Aren’t the boards irreconcilably different?

Well, no. No they are not. The above examples exemplify well an important realisation I have had whilst working, as teacher, tutor and examiner, with the full range of exam boards over the years:

The differences between the various GCSE and International GCSE/IGCSE exam set-ups are largely bureaucratic/administrative. In their fundamental approach, the boards actually aren’t that different.

This may surprise some readers. So let me explain.

Firstly, all GCSEs in England are accredited by Ofqual and share the same assessment objectives. Some of the exams are practically identical. Compare, for example, AQA’s English Language Paper 1 and OCR’s English Language Paper 2. Or, compare AQA’s Macbeth task with OCR’s Macbeth task. Blink and you’ll miss the minor differences.

Add to this the fact that Ofqual keeps the GCSE specifications from England on a very tight rein. They note that:

“We accredited new GCSEs to check that they covered the government’s expected curriculum and met the carefully designed rules around assessment we put in place. We can also be confident that grade standards between GCSEs offered by different exam boards align and that standards are maintained over time.”

The GCSEs in England then, I contend, are near-identical. The minor differences in timing or marks per question or question layout are just that, minor.

(The GCSEs in the devolved administrations are not covered in this article. I may do a deep dive into WJEC and CCEA assessments in the future.)

What about the international GCSEs? They are wildly different, aren’t they?

The International GCSEs, it is true, are not so tightly controlled by Ofqual. In fact, in recent years, Ofqual has cut the International GCSEs free. Ofqual stated, in April 2019, that “the awarding organisations that offer International GCSEs each decide the content for those qualifications and how that content is assessed, which may legitimately be different to GCSEs.”

Does this mean the International GCSEs exist as free-booting privateers, cruising international waters, making up their qualifications as they go along?

No. Of course not. The various boards offering International GCSEs have very strong incentives to keep their qualifications as close to the GCSE as possible. After all, a good GCSE in English Language (Grade 4/C or above) is one of the primary tools used by educational establishments and even employers to assess language competence. Having that grade on a CV means no scrambling around trying to get IELTS qualifications or having to do extra language tests. The GCSE opens doors and the International GCSEs aspire to do the same.

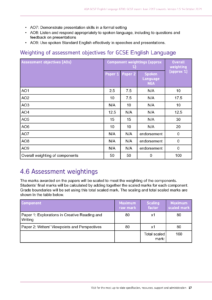

So, a close read of the GCSE and the various International GCSE English Language assessment objectives reveals a tight alignment in language. Take a look for yourself in the images below.

In fact, some of the assessment objectives are worded near-identically. Consider the below extracts from the English Language/First Language English specifications. The numbering is different but the wording is what’s important.

Reading:

- AQA GCSE: analyse how writers use language and structure to to achieve effects and influence readers (AO2).

- Cambridge IGCSE: demonstrate an understanding of how writers achieve effects and influence readers (AO1 R4).

- Edexcel International GCSE: analyse how writers use linguistic and structural devices to achieve their effects (AO2).

- OxfordAQA International GCSE: explain and evaluate how writers use linguistic, grammatical, structural and presentational features to achieve effects and engage and influence the reader (AO1 R4).

Writing:

- AQA GCSE: a range of vocabulary and sentence structures (AO6).

- Cambridge IGCSE: a range of vocabulary and sentence structures (AO2 W3).

- Edexcel International GCSE: a range of vocabulary and sentence structures (AO5).

- OxfordAQA International GCSE: select vocabulary appropriate to task, a range of sentence structures (AO2 W1, W2).

Looking at the specifications, we can also see that the weightings are also exactly the same: 50% marks awarded for reading and 50% marks awarded for writing.

Finally, a close look at marking and the awarding of grades, reveals that International GCSEs and GCSEs hardly differ at all. A November 2019 Government report found that, on average, pupils “achieved similar grades in their IGCSEs (Cambridge) and their GCSEs.” This suggests that, contrary to popular belief, there isn’t necessarily an obviously harder or easier or more generously marked GCSE or IGCSE to choose.

Now, this still leaves space for variation. An exam board could choose, for example, to test writing by setting a timed sonnet writing task, or a social media message task, or a instructions manual writing task. An exam board could set an extract from Beowulf or lyrics from Adele’s latest song to test reading.

Are they going to do that though? Let’s leave aside for now the questionable utility of teaching and assessing sonnet writing, as tugging too hard at the ‘utility’ thread could cause a lot of unravelling – why, for example, are extracts from 19th century non-fiction texts set in a test of modern Standard English? Utility, although important, is not the best measure here.

Instead, I propose, that the true measure is: how willing is an exam board to be completely different in its approach to English assessment? How willing is an exam board to open itself up to suspicion and hostility (“why are you teaching my child pop lyrics?” “how is Beowulf relevant to getting a job at the Bank of England?”) which would leave the market wide open for a board that promises a ‘traditional’, ‘rigorous’ approach?

Not very willing at all, is my answer. There appears to be no incentive for an exam board to try to single-handedly re-imagine the traditions of English assessment in England, Wales and beyond. The international boards have the freedom to do so, but they don’t. In fact, CAIE have confirmed that they “commit…to align the standard of Cambridge IGCSE with equivalent qualifications taken in England.”

Now, it’s true that some boards do aim to present themselves as radical and new. However, a close look at their assessment material reveals that they are really just presenting the same assessments under a light dusting of radical-sounding rhetoric. The Edexcel GCSE English Language 2.0 presents itself as “engaging,” “relatable,” “less traditional,” “real-world,” “fresh,” and “new” (and even “2.0,” though that sounds a little 2005) yet the sample assessment materials are very familiar: reading comprehension questions, non-fiction writing task, creative writing task.

So, it turns out English assessment at age 16 is largely similar in approach, then?

If you’ve read this far you will already know my response to this: YES!

Because, the exams are all assessing the same thing: capability in reading and writing modern Standard English. This means that all exam boards end up setting some combination of the below tasks for English Language:

- prose creative writing

- prose non-fiction writing

- fiction reading (assessed through short and mid-length essay-style answers)

- non-fiction reading (assessed through short and mid-length essay-style answers)

And all exam boards end up setting some combination of the below tasks for English Literature:

- Shakespeare essay on an extract and/or the entire play

- 19th century novel essay

- modern (20th century onwards) text essay

- poetry analysis essay, often including comparison

- unseen poetry analysis essay, often including comparison

This, as already argued, also means that learning resources can usefully be deployed, mutatis mutandis, across different boards.

This understanding also helps to de-mystify English assessment and is particularly helpful too for parents who are often completely in the dark. My message is always: “don’t worry – they’re not that different.” Ultimately, this attitude can also be very clarifying and calming for students, especially those who have changed schools, and possibly boards, a number of times and may feel scared about now having to follow the specification of a new board.

Now, I acknowledge, having come all this way, that some will never agree with the arguments set out in this article:

- some just feel more comfortable with one exam board rather than another.

- some find even small changes in the administration of exams to be very destabilising.

- some may have incentives to back one board over another.

- some may only ever have worked with one board and will have no familiarity with other boards.

Fair enough. I know I can’t persuade everyone. However, if you are a nervous student facing a rapidly approaching GCSE English Language exam and you find creative writing difficult, pick up a copy of my creative story model answers or my description writing model answers.

If you are facing a Macbeth exam and you don’t know your Banquo from your dramatic irony, pick up a copy of my Macbeth model answers.

If you have never given much thought to writing at length about real-world issues, and your exam is approaching in which you will have to write in-depth about real-world issues, take a look at my collection of non-fiction model answers.

They are tried and tested with real students and – they work.